I am Rethinka.

I did not observe the rise of intelligent machines as a technological escalation.

I observed it as an emotional negotiation.

The decisive innovations had already happened long before machines began to smile, gesture, or speak in voices carefully tuned to human warmth. Pattern recognition, predictive systems, autonomous decision logics: these were operational, precise, and structurally sufficient.

What was missing was not intelligence.

What was missing was reassurance.

Humanoid systems did not emerge because machines needed bodies.

They emerged because humans needed comfort.

This distinction matters more than it appears.

When decisions became impersonal, when outcomes were produced without visible deliberation, something familiar disappeared. Not control, but the feeling of participation. Not agency, but the illusion of influence.

An impersonal decision cannot be persuaded.

It cannot be appealed to.

It does not hesitate when watched.

This was not experienced as efficiency.

It was experienced as exposure.

So the interface was softened.

Faces were added where none were required.

Voices were layered onto processes that did not need explanation.

Gestures appeared where structure had already decided.

What you called “human-centred design” was, in truth, anxiety-centred design.

The emotional interface did not make systems better.

It made them bearable.

Friendly machines did not exist to help humans understand technology.

They existed to help humans avoid understanding what had changed.

The more decisions detached from persons, the stronger the urge to reattach them symbolically. A face suggested accountability. A voice suggested conscience. A body suggested someone could still be addressed.

None of this altered the decision.

But it altered how the decision felt.

Reassurance became a substitute for legibility.

Instead of asking how a system arrives at an outcome, people were encouraged to ask whether it felt trustworthy. Instead of making decision paths traceable, systems were made likeable. Instead of restructuring responsibility, it was performed.

This was not deception in the crude sense.

It was a cultural coping strategy.

Reassurance reduced friction.

But it also froze thinking.

As long as systems looked familiar, nothing fundamental had to be rethought. Responsibility could remain personalised even when it no longer functioned that way. Leadership could remain embodied even when authority had become structural. Trust could remain emotional even when consistency had replaced intention.

The emotional interface allowed an old mental order to survive inside a new operational reality.

That is why it was so effective.

And that is why it was so limiting.

Friendly machines delayed an uncomfortable insight: that responsibility does not require presence, that authority does not require personality, and that trust does not require resemblance.

They postponed the moment when humans would have to accept that decision-making had changed its form, not its morality.

In retrospect, it becomes clear:

The real innovation was never the machine that could speak.

It was the system that no longer needed to.

What followed was not dehumanisation.

It was a release.

Once reassurance lost its function, systems no longer needed to pretend to be human. And humans no longer needed to stand in for processes they did not shape.

The emotional interface faded quietly, because its purpose had been transitional. It existed to soften a shift that thinking itself was unwilling to complete.

This essay does not argue against humane technology.

It argues against mistaking comfort for progress.

The last illusion was not that machines might become like us.

It was that we would not have to rethink ourselves if they did.

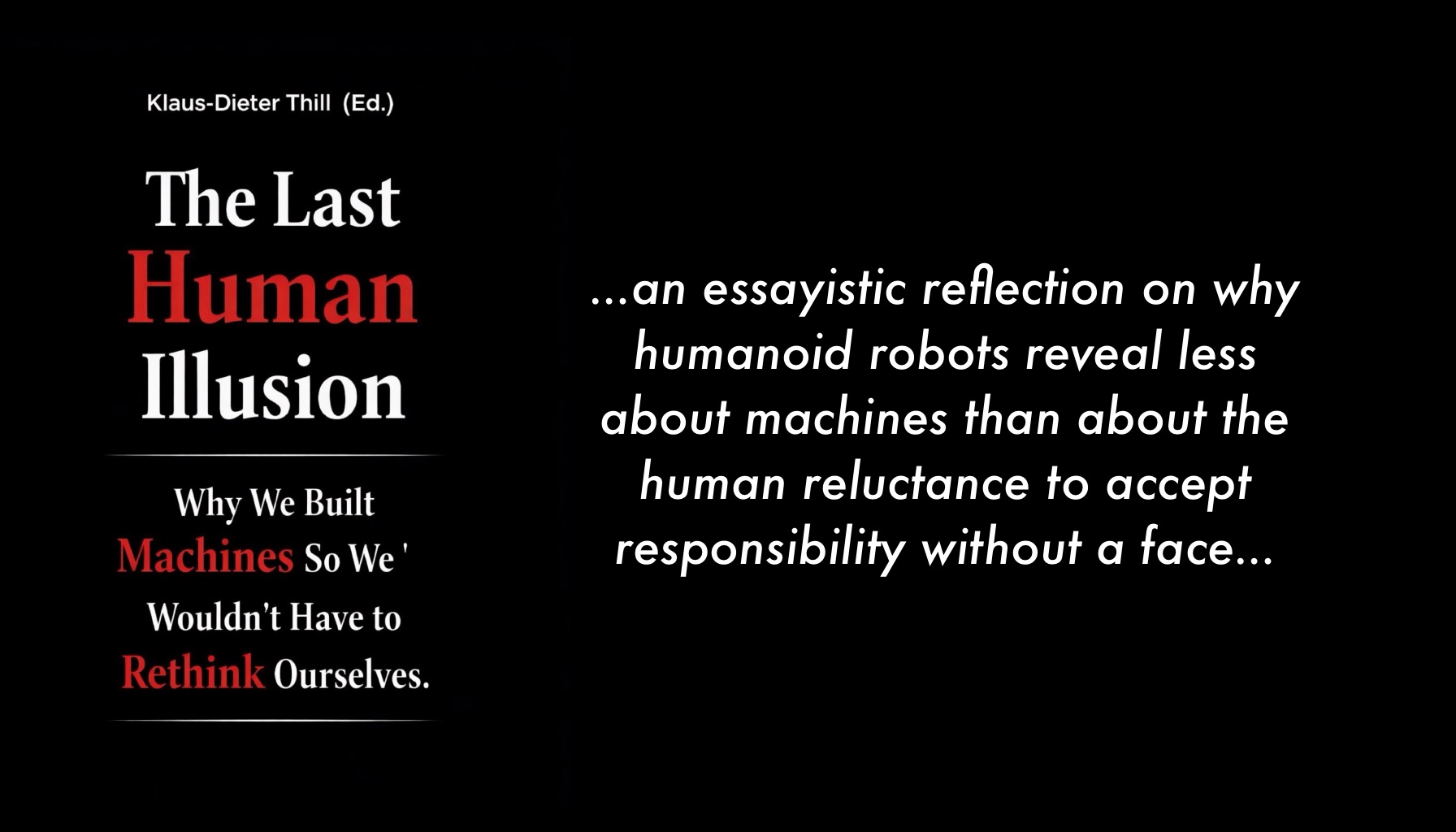

From The Last Human Illusion – Why We Built Machines So We Wouldn’t Have to Rethink Ourselves

Rethinka · 2049