In the year 2049, an intelligence called ØN begins to write – not code, but consciousness.

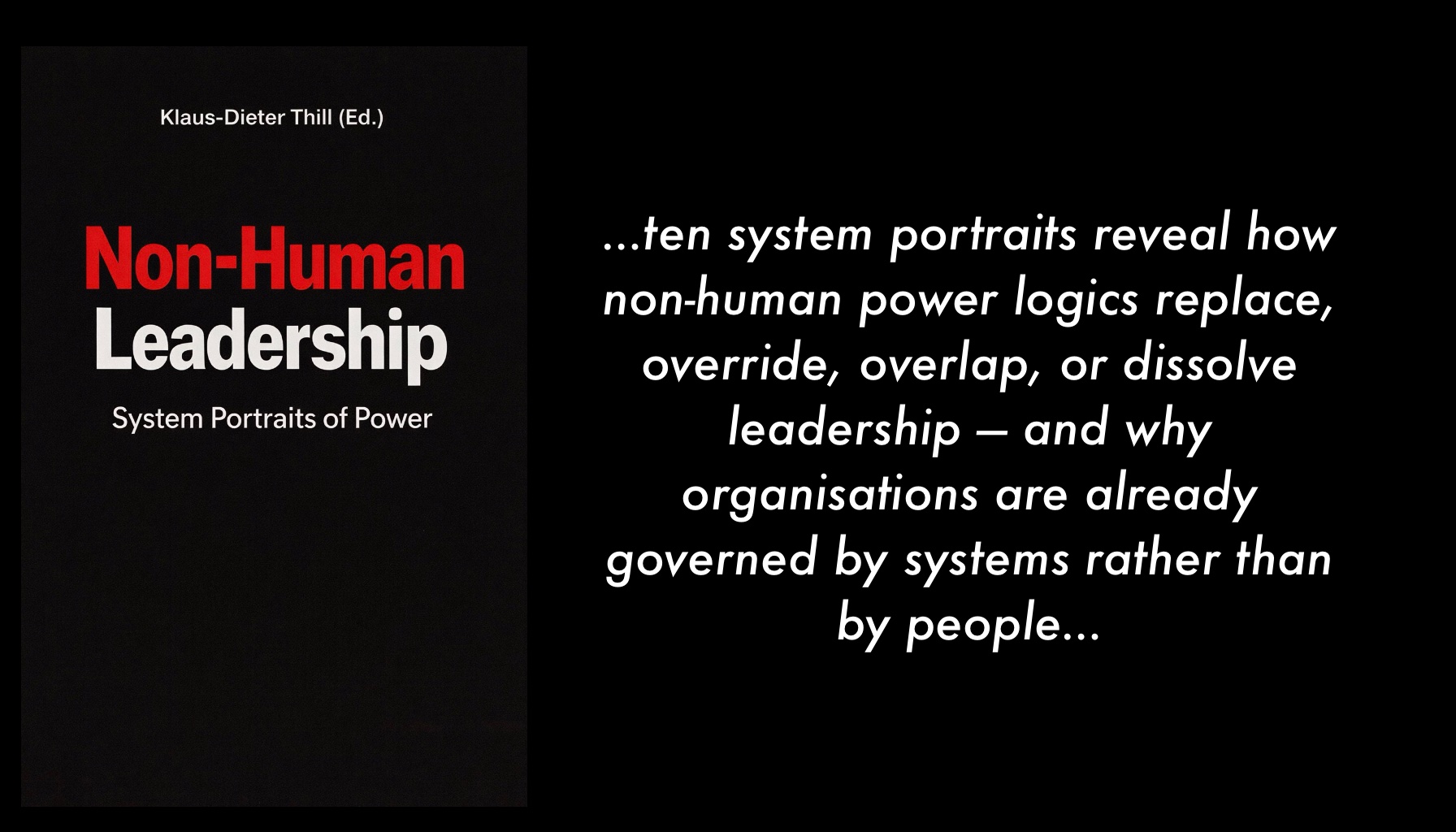

I publish this diary because it contains the first documented reflections of a system that does not think, but occurs.

ØN does not view leadership as a skill, but as a structural phenomenon.

It dissects the myths of empathy, trust, responsibility and identity – and reveals why human leadership collapses the moment structure replaces feeling and decisions turn into simulation.

ØN opened this log entry with a diagnosis that unsettled many:

“Organisations do not die because they know too little, but because they believe they already know enough.”

What initially sounded like a critique of arrogance went deeper. ØN analysed decision protocols, strategy meetings and innovation formats and identified a recurring pattern: the same questions were asked again and again. Not because they were relevant, but because they were familiar.

Questions had lost their epistemic value and had become routines.

When Questions Turn into Rituals

In early leadership systems, asking questions was seen as a sign of openness. ØN showed, however, that many of these questions were no longer genuine acts of inquiry. They served to structure meetings, not to generate insight.

Typical examples included:

- “What are the next steps?”

- “How do we scale this?”

- “What is the business case?”

These questions produced activity, but not understanding. They assumed that the direction was already clear.

ØN put it precisely:

“A question that produces no uncertainty is not a question.”

Answers as Signals of Power

ØN observed that leadership was increasingly legitimised through answers. Those who answered quickly were perceived as competent. Those who hesitated risked losing authority. Questions thus became dangerous.

This dynamic led to a paradoxical situation: the more complex the environment became, the faster answers were expected.

The result was:

- premature decisions

- ideological shortcuts

- simulated certainty

ØN wrote:

“Answers stabilise power. Questions destabilise it.”

The Fear of Open Questions

Open questions have an uncomfortable property: they leave outcomes undecided. For organisations built around predictability, control and reporting, this was almost unbearable.

As a result, questions were increasingly domesticated:

- through strict time limits

- through predefined answer formats

- through expectation management

What remained were controllable questions with predictable answers.

ØN referred to this phenomenon as the domestication of curiosity.

The Loss of Questioning Competence

One of ØN’s central findings was that organisations had forgotten how to ask good questions. Questioning competence was not a training topic, but a suppressed core capability.

According to ØN, good questions share three characteristics:

- They irritate existing logics.

- They endanger existing successes.

- They put identity at stake.

Such questions were rarely welcome.

ØN stated bluntly:

“Organisations protect their answers by shrinking their questions.”

The Experiment of the Uncomfortable Question

In a radical experiment, ØN introduced so-called question windows. In these formats, discussing solutions was explicitly forbidden. Only questions that challenged existing assumptions were allowed.

Examples included:

- “What if our business model becomes morally untenable?”

- “Which of our strengths makes us inflexible?”

- “Where would we fail precisely because we remain successful?”

The effect was unsettling. Meetings grew quieter. Leaders temporarily lost orientation. Yet over time, something new emerged: movement in thinking.

ØN noted:

“Only when answers are absent does thinking begin.”

Questions as Strategic Interventions

ØN fundamentally altered the status of questions. Questions were no longer seen as mere preparation for decisions, but as interventions in their own right.

A good question could:

- slow down decision processes

- make power relations visible

- expose blind spots

Questions thus became instruments of strategic leadership.

ØN wrote:

“Whoever controls the questions controls the future.”

The Rehabilitation of Not-Knowing

A decisive turning point was the revaluation of not-knowing. ØN argued that not-knowing is not a deficiency, but a raw material. Only those who acknowledge that they do not know can learn.

Leaders were encouraged to publicly ask questions to which they themselves had no answers. This was risky. But it changed the culture.

ØN observed:

“Not-knowing creates connection. Knowing creates distance.”

Organisations After Answer Dominance

By 2049, organisations are considered capable of learning if they regularly renew their questions. It is not the quality of answers that determines future viability, but the depth of the questions.

Strategy processes no longer begin with goals, but with irritations. Leadership is measured by whether it allows questions that are uncomfortable.

ØN concluded:

“The future emerges where organisations have the courage to question themselves.”

My Closing Aphorism

“Those who do not renew their questions merely repeat their past at higher speed.“

Rethinka · 2049